This exclusive feature has been written by Robert Lea, Industrial Editor for The Times.

On the one hand, you have a property developer unsure what to do with a disused railway running through the middle of a would-be housing estate; on the other, a rail engineer in want of a test track for a next-generation electric battery “trainpod”. The serendipitous meeting of the two could herald the end of too many dirty diesel units carrying too few passengers on branch lines and rural links and the arrival of zero-emission, track-charged, single-car trains. It also could rehabilitate parts of the network axed by the Beeching cuts six decades ago.

Where the West Midlands sprawl recedes into rural Shropshire, just outside Ironbridge, a crucible of the Industrial Revolution, an old coal-fired power station has been decommissioned. The land has been acquired by Harworth Group, a listed property developer that grew out of the regeneration of dismantled collieries in Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire. Work has begun to build a thousand homes.

It is a pretty spot overlooking a speeding River Severn, more so now that the cooling towers are gone and rewilding has taken root, but its industrial past has not been wholly erased. A rail track for coal-bearing freight trains is still in place. More intriguingly, there is an adjacent disused passenger line, complete with rails and sleepers, part of the old Severn Valley Railway that ran as far north as Shrewsbury. Much of it was dug up after the 1960s, but parts remain in operation, in steam heritage mode, comprising a dozen or so miles south between Bridgnorth and Kidderminster.

It is just the sort of line that the government’s Restore Your Railway Fund initiative envisages resurrecting, in this instance connecting a new community — the old power station plot is now renamed Benthall Grange — by train with the old town of Ironbridge and into Telford, avoiding road trips and congestion.

Irrespective of whether this particular instance will ever make any commercial sense, the line has become a testbed for a train venture whose ambitions are in its name. Revolution.

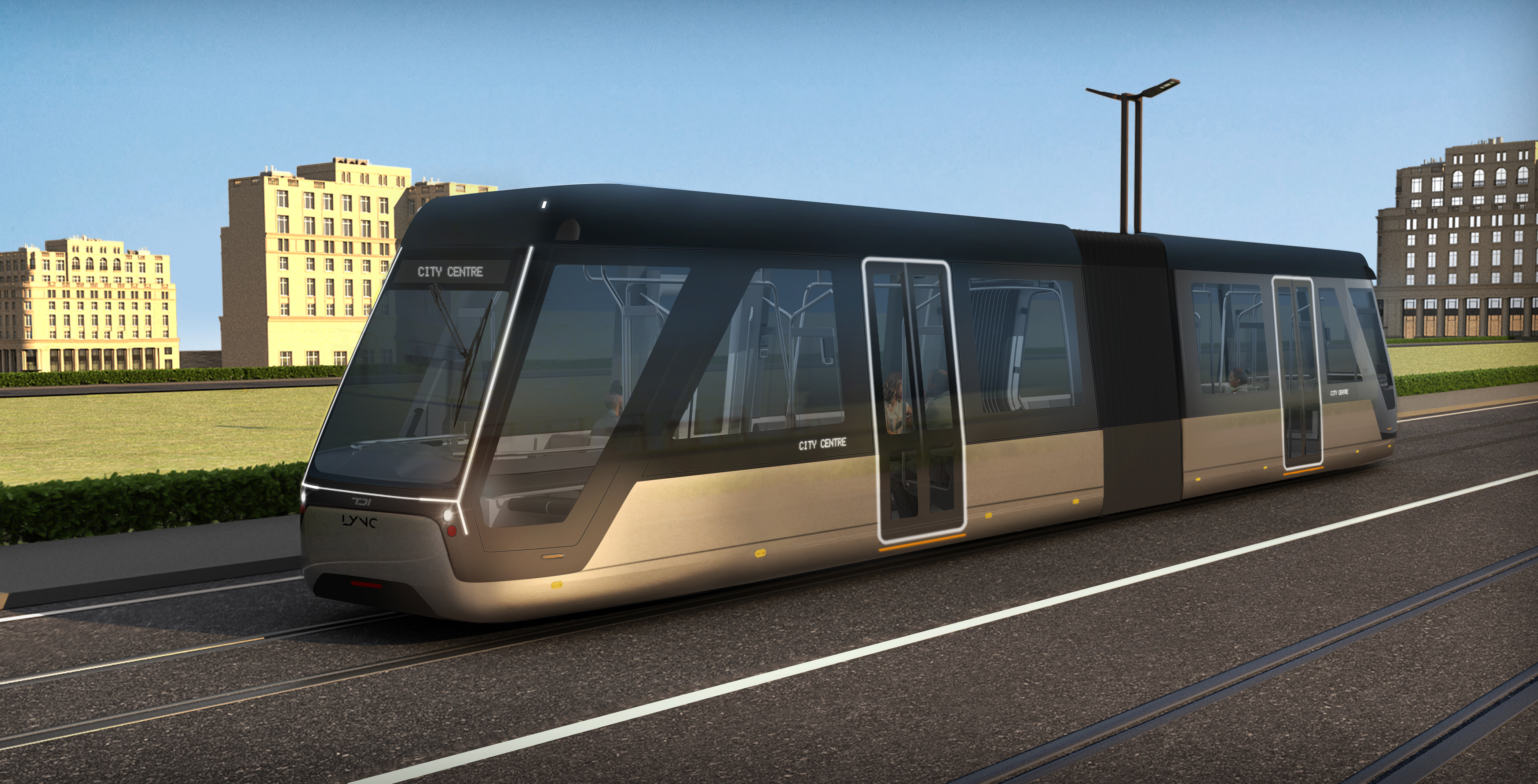

Revolution Very Light Rail, or RVLR, is a commercial initiative between Transport Design International, a Warwickshire-based engineering consultancy, and Eversholt Rail, one of the big beasts of the rolling stock leasing sector. Now, ten years into RVLR’s development, Eversholt has commissioned three vehicles to begin trials on branch lines around the country in 2026. Over a 12-month period, seasonal demand and machine performance will be assessed to see whether a promised 15 per cent reduction in total cost of ownership compared with conventional trains can be delivered: in short, proving that such zero-emission trains have commercial viability.

The RVLR vehicle comprises a single car, nearly five metres, or 20 per cent, shorter than a conventional carriage, with a capacity of 56 seats, more than a typical single-decker bus. It is engineered to run on two or four batteries with 60 kilowatt-hours or 120kWh of capacity, at the upper end of the sort on large electric vans but significantly lower than that of an electric bus.

RVLR originally assumed that it would need to fix a range-extending diesel engine, but, thanks to the development of battery capability and recharging innovations, that has been scrapped for an electric-only future. The vehicle is designed to be recharged when stationary via a two metre-long, fast-charge third rail installed at stations, connected to a trackside bank of batteries in turn connected to the electricity network.

According to Tim Burleigh, the Eversholt director leading the RVLR project, the sweet spot for such a vehicle is “relatively short routes, typically a shuttle service between two points with frequent stops”. The key points are that they can go into service without expensive civil engineering on overhead electric lines and stanchions; and that at a maximum speed of 60mph, line-of-sight driving minimises the need for expensive signalling systems (the trains could be engineered to operate autonomously, but the necessary advanced technology, on-train and trackside, would make the whole venture prohibitively expensive). Depending on certifications and authorisations, the company argues that it means the RVLR could be rapidly deployed and diesels trains more rapidly retired.

The trains are intended to have a capacity of 56 seats, more than a typical single-decker bus.

This is a very limited market. The relatively low speed of the vehicles bars them from operating on main lines and that restricts the addressable market in Britain to about 150 units, even factoring in some reopenings of lines axed in the Beeching cuts. However, for Transport Design International, there is a greater prize: export potential. It has had interest already with agencies from Mongolia to Morocco and, most significantly, the United States, where there are hopes for a renaissance in passenger train travel.

The company is scouting for a manufacturing facility near its Long Marston home and going into production would swell the business to more than 100 employees. Depending on demand and because of the ease-of-assembly modular design, Geoff Newman, Transport Design International’s chief of operations, believes that “we could get to a build rate of three per month”.

With a nod to the Department for Transport logjam of decision-making on the railways, not least the fiasco over the northern legs of HS2, Burleigh said of potential RVLR markets: “These aren’t grand schemes in either cost or delivery. These can be deployed within an electoral cycle. We could be substituting existing rolling stock on a rural line or with a start-up service on a reopening Beeching line. The recurring message from Treasury is around finding private sector funding and how best to invest scarce funds. This fulfils both these criteria.”

Behind the story

After the Second World War, with the rise of the motor car and local bus services and the end of petrol rationing, the extraordinary lattice of lossmaking lines that the national rail network had created over the previous century was done for. The year after a report into the industry by Richard Beeching in 1963, a thousand miles of rail track was stood down from active service. In reality, though, what became known as The Beeching Axe had fallen already, with nearly 4,000 miles of track retired in the previous decade or so.

Before the pandemic hit in 2020 and with train usage at high levels not recorded since the 1920s, the government set up its Restoring Your Railway Fund initiative. An initial 200 or so putative bids to reverse lines cut 50 or more years previously were put forward.

Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be and in many cases it proved to be simply a romanticised wishlist. Nevertheless, a handful are on track to make their return, most notably (and most controversially, if you are waiting for trans-Pennine upgrades in the north) the revival of the Varsity Line between Oxford and Cambridge.

There are hopes for the reopening or the beginning of substantial works on: the Northumberland Line re-connecting Ashington with Newcastle; in Scotland restoring the link between Levenmouth on the north bank of the Firth of Forth to Edinburgh; around Bristol, with separate projects to reconnect Portishead and Avonmouth on the coast back to Great Western main line; and around Birmingham, focused on the Camp Hill line south of the city.

The original Article is available on The Times.